(Bitter) Lessons from Scaling Machine Learning Interatomic Potentials

TL;DR: We tested whether a plain transformer encoder (no equivariance, no periodic boundary conditions) can learn interatomic forces as data & params scale vs. EquiformerV2. EqV2 followed clean power laws and hit much lower loss. My transformers plateaued hard while learning forces, but observing their attention weights shows they learned graph structure as an emergent behavior. I share the wins & failures.

For EquiformerV2:

Code is open sourced here. Work was done alongside Eric Weiner, Park Szachta, Advait Gosai, and Kyle Chu.

A little over a year ago I got pretty interested in training neural networks that can learn physics from data. Around the time machine learning interatomic potential (MLIP) models were becoming popular. These models broadly take as input a material’s atomic configuration and predict properties related to its potential energy. All the papers I was reading had great results, but I felt they were selling an incomplete story because they were missing scaling information. To me, understanding how a model scales is perhaps the most important factor and having just 1 datapoint of a final test loss was insufficient to understand how any architecture would stand the test of time.

We tried to investigate whether vanilla transformer encoders, given sufficient data, could learn to predict material properties as well as architectures explicitly equivariant architectures, like EquiformerV2 (EqV2) [1]. Inspired by the Bitter Lesson [2], my hypothesis was that that transformers would scale more slowly than specialized architectures but that their scaling laws [3][4][5] would hold out over more orders-of-magnitude (OOM).

We failed to stably train transformers most likely due to the lack of pretraining and featurization I chose. I still learned a great deal along the way, and found power laws for EqV2.

Why the math makes sense:

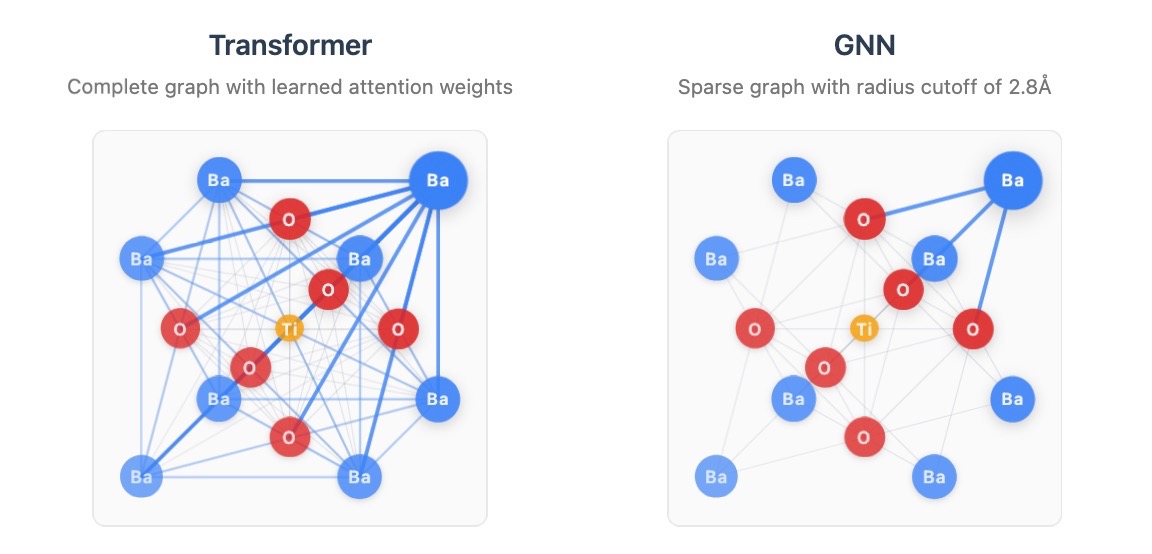

A Transformer is a graph neural network (GNN) on a complete graph with learned edge weights [6]. A graph in a GNN is created through a rule, either a known relation between nodes i.e. this paper cites another or a cutoff i.e. this atom is too far from the other so we assume they won’t interact.

A simple argument between the two architectures is that they fall into the bias - expressivity tradeoff. My take is that since self-attention on a fully connected graph is mathematically equivalent to message passing [6] it should be able to learn weights between atoms without having to describe them.

Task and Dataset

MLIPs are trained to take in a set of atoms and their positions to predict the structure’s energy and typically the forces on the atoms as well as the structure’s stresses.

A common criticism of MLIPs trained on Density Functional Theory (DFT) calculations is that those datasets are relaxed structures around 0K. This means that they’re not physically relevant in most cases to us because we don’t live around 0K.

The Open Materials 2024 (OMat24) [7] dataset is a 110 million crystal structure dataset that addresses this problem by focusing on including non-equilibrium (high temperature, structurally perturbed) samples. It’s also one of the largest datasets of its kind.

Sin #1: Transformer featurization

In my attempt at training transformers I wanted to use as few inductive biases as possible. i.e. no equivariant features, no invariant features, no periodic boundary conditions. This was an attempt to learn everything from the data + augmentation, regardless of sample efficiency.

I used a standard embedding layer for atom types to give the model a dictionary lookup of what each atom is across different structures. This was important because the model needed to understand that each atom is the same in different structures but is modified by its context, similar to how each word is the same in different sequences and is modified by its context. The 3D positions were concatenated with the embedding vector because I thought the model might have an easier time disentangling meaning vs. saving parameters by adding the positions to the embeddings.

\(\begin{array}{c@{}c@{}c} \text{Input feature matrix: } & \left[ \begin{array}{ccc|ccc} e_{11} & \cdots & e_{1d} & x_1 & y_1 & z_1 \\ \vdots & \ddots & \vdots & \vdots & \vdots & \vdots \\ e_{N1} & \cdots & e_{Nd} & x_N & y_N & z_N \end{array} \right] & \in \mathbb{R}^{N\times(d+3)} \\[-2ex] & \begin{array}{c@{\mkern8mu}c} \underbrace{\hphantom{e_{11}\ \cdots\ e_{1d}}}_{\text{atomic embeddings}} & \underbrace{\hphantom{x_1\ y_1\ z_1}}_{\text{positional encoding}} \end{array} \end{array}\)

\(\begin{array}{l} \text{Input feature matrix:} \\[2ex] \left[ \begin{array}{ccc|ccc} e_{11} & \cdots & e_{1d} & x_1 & y_1 & z_1 \\ \vdots & \ddots & \vdots & \vdots & \vdots & \vdots \\ e_{N1} & \cdots & e_{Nd} & x_N & y_N & z_N \end{array} \right] \\[-2ex] \mkern20mu\underbrace{\hphantom{e_{11}\ \cdots\ e_{1d}}}_{\text{atomic embeddings}} \mkern24mu \underbrace{\hphantom{x_1\ y_1\ z_1}}_{\text{positional encoding}} \end{array}\)

This was purposefully not a rotationally invariant featurization as I wanted to see if the model could learn this through augmentation. It also did not account for the fact crystal structures are periodic, which means that forces on atoms can come from adjacent cells. My findings are that this featurization led to the model learning global structure energy and stresses well, but not 3D per-atom forces. This isn’t to say that forces weren’t learned at all, but they were certainly not comparable to EquiformerV2.

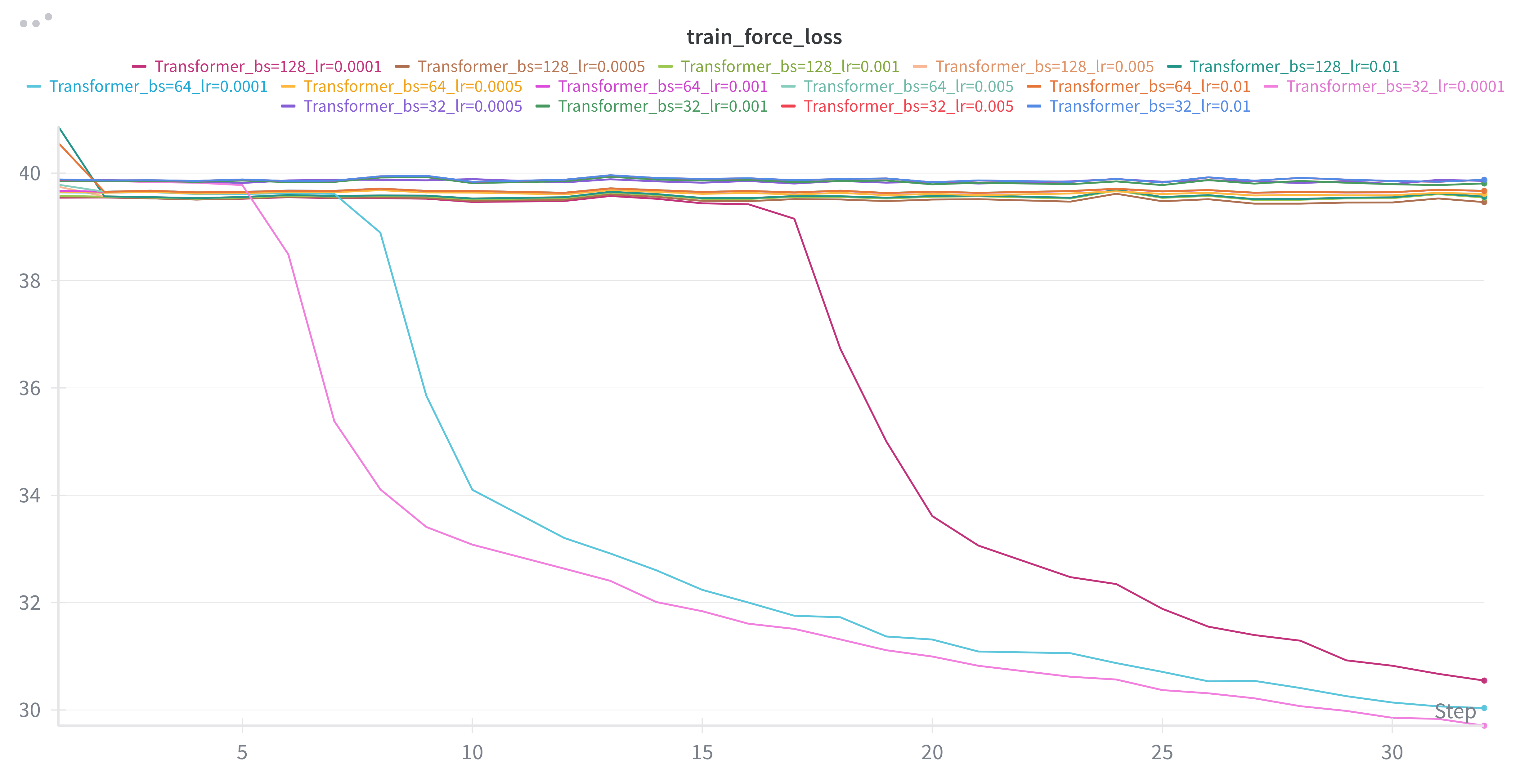

I got stuck with this phenomena of an apparent plateau in force loss only for certain hyperparam configs. There were other runs that would break through but still plateaued much higher than the EqV2. I suspect that training stability had a role with the former, and ultimately the lack of periodic boundary conditions impacting the latter.

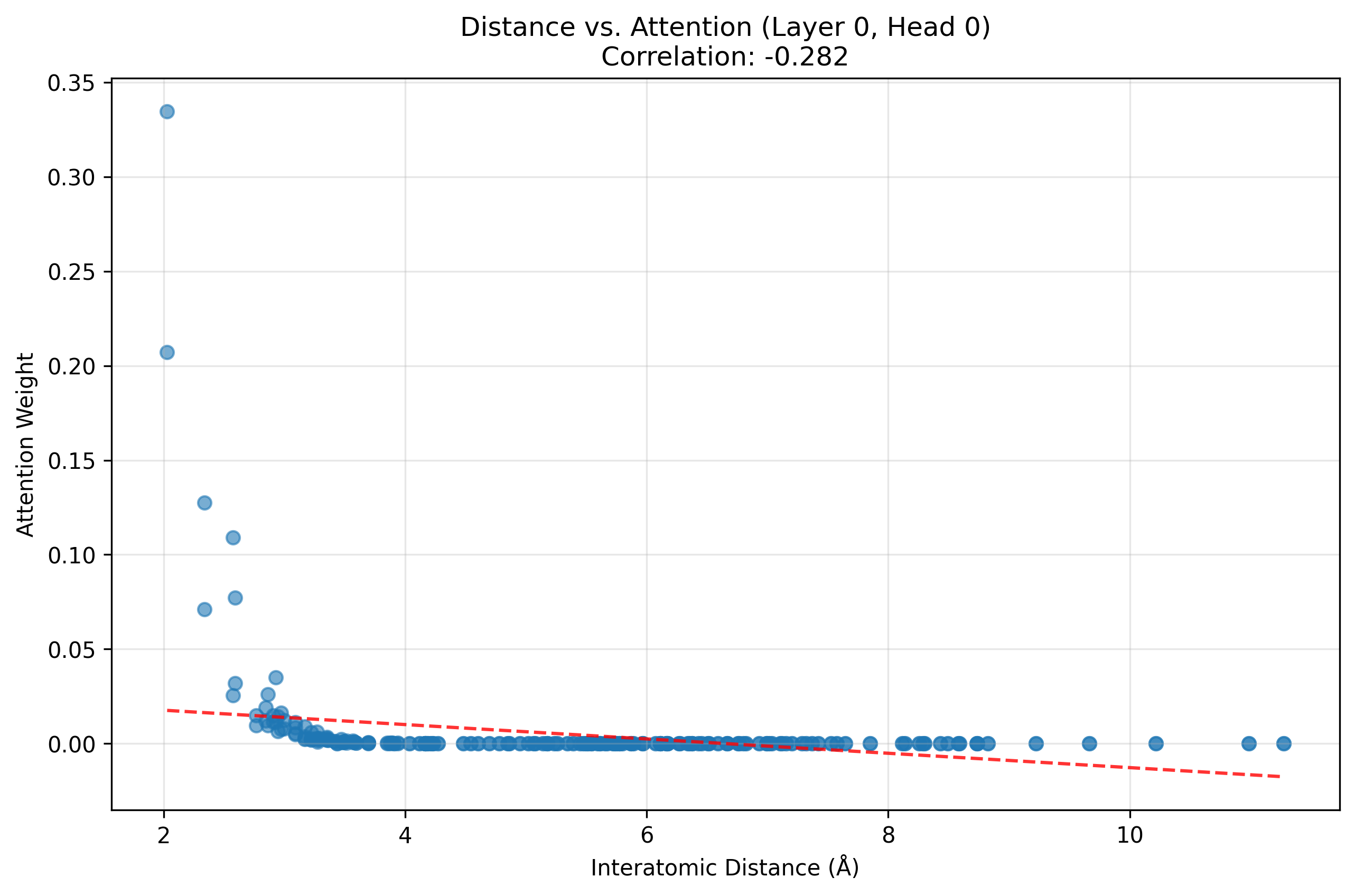

However, I did notice the transformers were learning physically meaningful attention patterns without it being an explicit task.

Inspecting the first layer and head of the transformer shows a learned inverse relationship between the attention weights and interatomic distances, which is physically correct. This overcomes the inflexibility of a GNN’s graph cutoff.

Tough lessons learned:

- Transformers probably would have performed better if pretrained to learn graph structure and then finetuned to predict material properties

- The models just want to learn and given enough parameters the loss will go down even if they aren’t learning the right thing.

- If scaling behavior doesn’t appear in smaller OOMs it’s unlikely it will magically appear later

Sin #2: Not starting with individual experiments

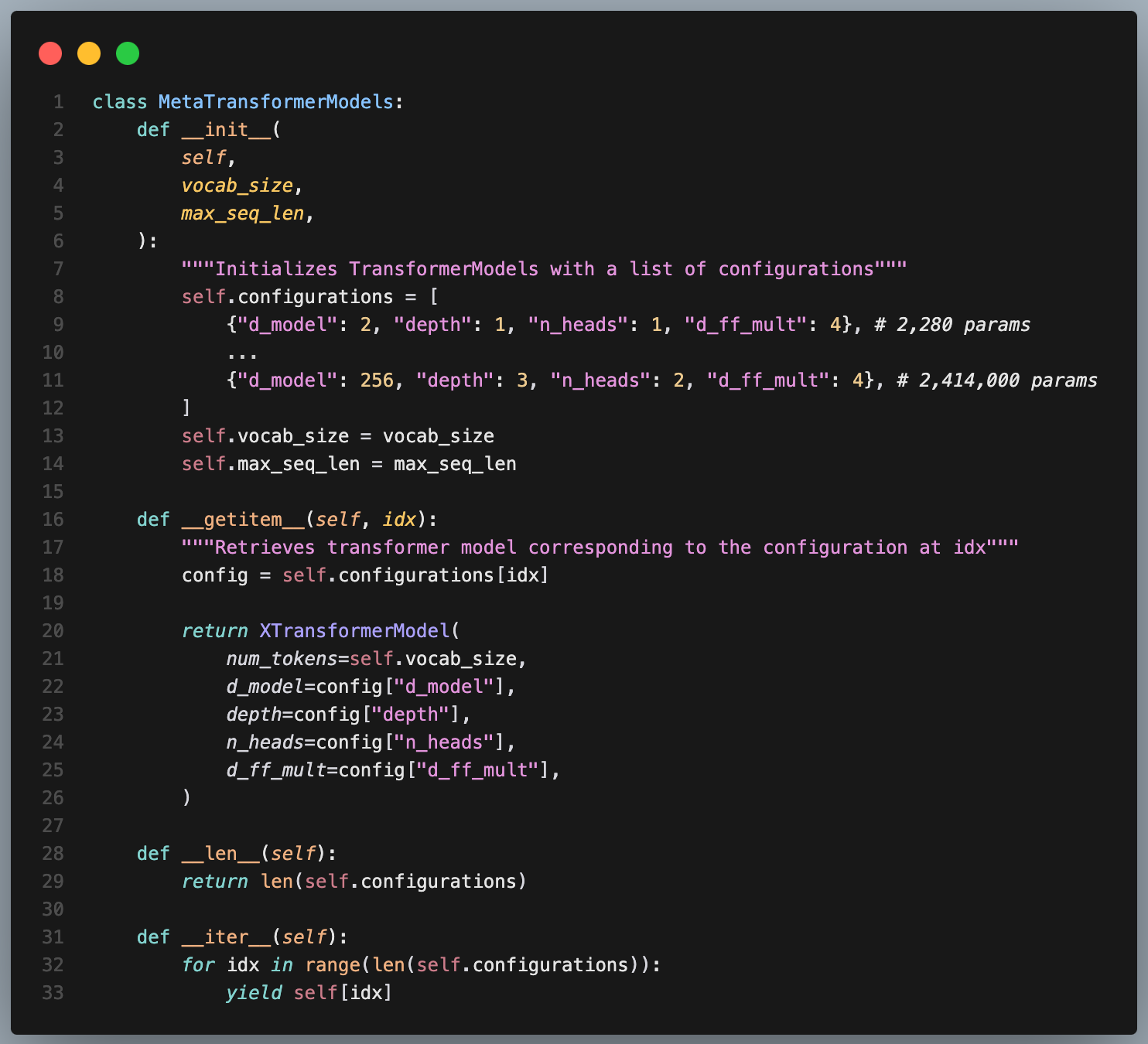

Instead, I rushed to create a more complex set of scripts that would automatically run scaling experiments over multiple OOMs. I came up with what I thought was a clever way of iterating through models:

On paper this sounds great to iterate over model sizes and lazily instantiate them, but in practice each OOM brings nuance and unexpectedness in behavior through e.g. hyperparameter sensitivity like early stoping. Instead, I should’ve started with small manual overfitting experiments and gradually increasing the parameters and data [8].

Sin #3: Not starting with a small, in-memory, dataset

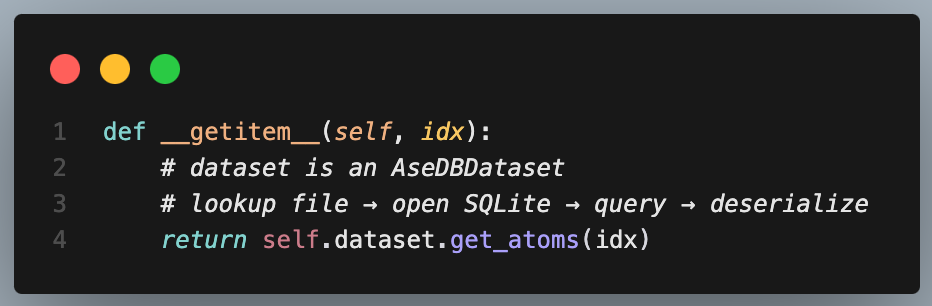

Over all the experiments I ran I found that dataloading was typically the bottleneck in training time. This is an example of a bad dataset class I wrote. The devil is in the details because the AseDBDataset.get_atoms(idx) call looks like a simple getter but is actually doing disk I/O.

Bad approach ❌

The result is that all of this work repeats every call:

- With random shuffling causing worst-case random disk access

- Across multiple worker processes (each with their own DB connections)

This is painful.

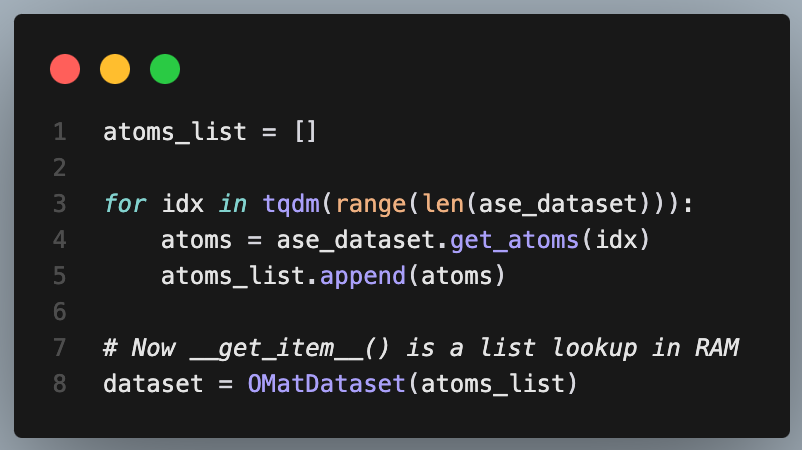

Better approach ✅

A very simple solution is to start experimenting with a very small dataset and iterate through it completely to cache it before training.

At a small dataset scale the first approach didn’t matter. But it wasted a lot of time as I scaled the dataset size.

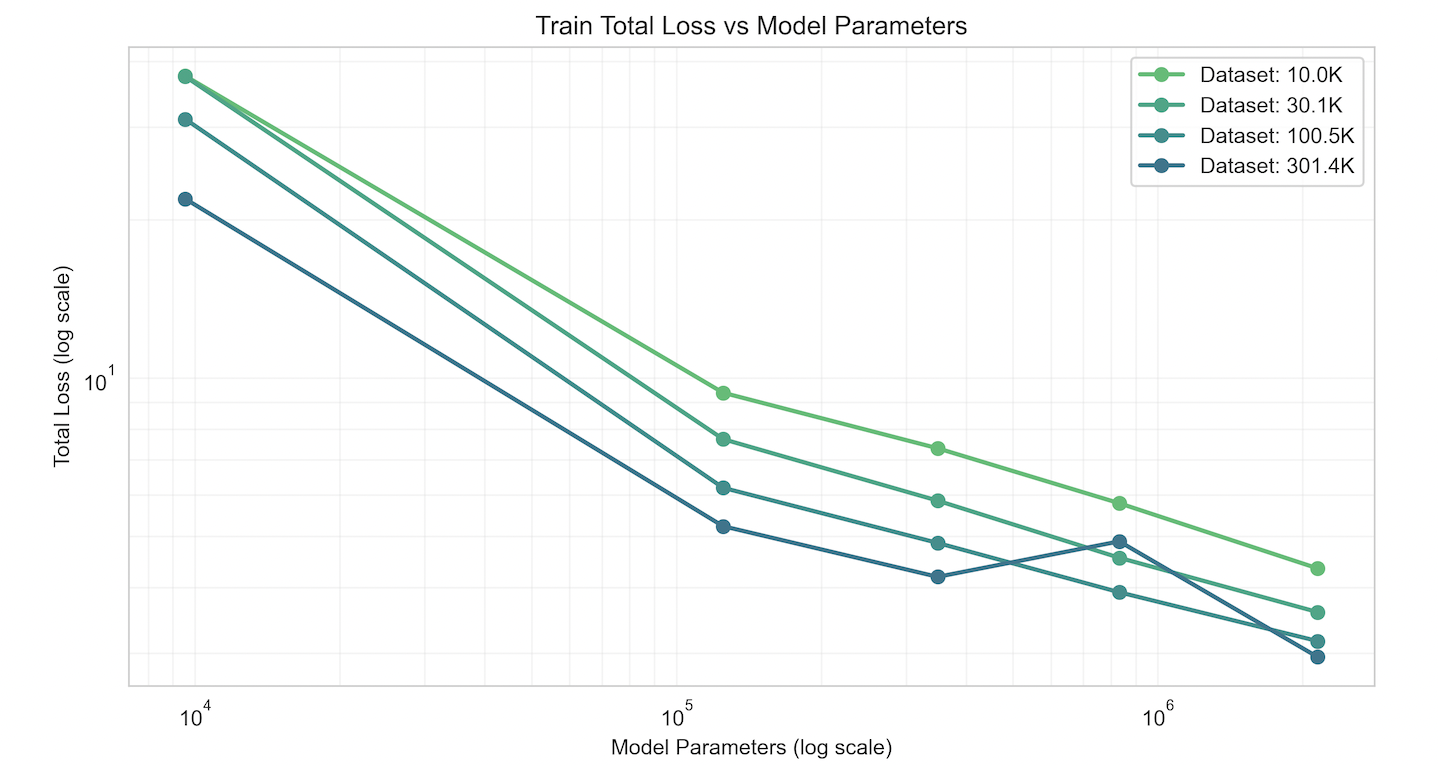

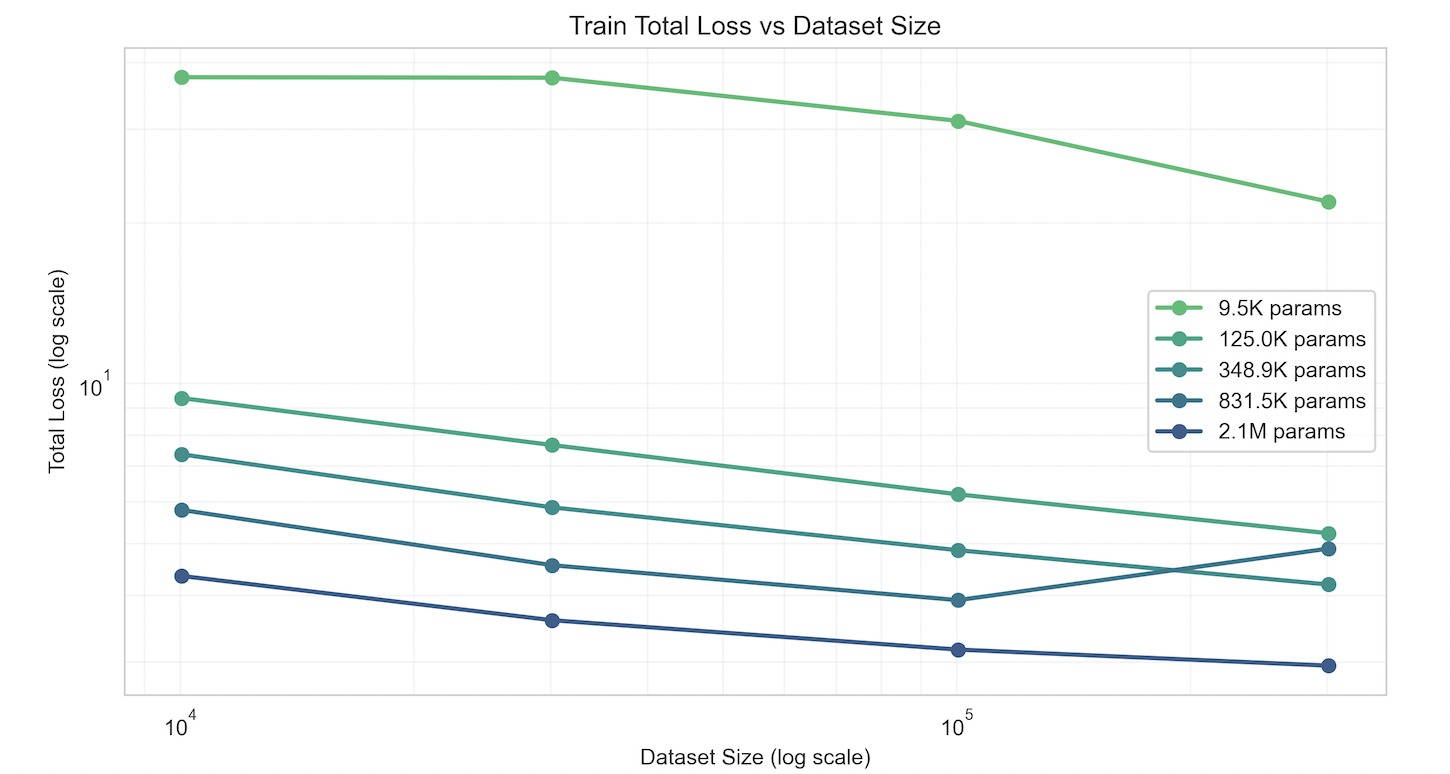

Win #1: Some EquiformerV2 results

Takeaways:

- Demonstrated power laws

- Data scaling shows diminishing returns compared to param scaling

- Identified compute-optimal training configs with a real pareto frontier

- Data and training pipeline worked for EqV2, so there was something inherently wrong with the transformer

Win #2: Making an inference visualization tool

This ended up being a very useful debugging tool to understand how the models were behaving. For example as a sanity check it was nice to see the transformer wasn’t only predicting 0 forces nor the mean of the dataset, and also that models were learning smaller magnitude forces as well as larger ones.

Win #3: Making a scaling law experiment run tool

This tool helped group families of runs and studying their behavior on the same plot. Before training any models I established naive (no deep learning) baselines that would help understand the loss number. The three baselines were:

- Loss while predicting 0 everywhere

- Loss while predicting the mean of the dataset everywhere

- Loss from a k = 1 nearest-neighbor Markov model

Win #4: Getting to talk to John Jumper about scaling AlphaFold

I think my life peaked a little when I got to have a pizza and a beer with John Jumper at the YC AI Startup School and pitch him this unfinished research.

References:

- [1] EquiformerV2 - Liao et al., 2023

- [2] The Bitter Lesson - Richard Sutton, 2019

- [3] Scaling Laws for Neural Language Models - Kaplan et al., 2020

- [4] Deep Learning Scaling Is Predictable, Empirically - Hestness et al., 2017

- [5] A Solvable Model of Neural Scaling Laws - Maloney et al., 2022

- [6] Neural Message Passing for Quantum Chemistry - Gilmer et al., 2017

- [7] Open Materials 2024 (OMat24) Dataset - Meta AI, 2024

- [8] A Recipe for Training Neural Networks - Andrej Karpathy, 2019

- Training Compute-Optimal Large Language Models (Chinchilla) - Hoffmann et al., 2022

- Naturally Occurring Equivariance in Neural Networks - Olah et al., 2020