Universal Mask Finding

Preface

I write using analogy of working for Willy Wonka’s chocolate factory to demonstrate that this method could be used in any manufacturing context that uses computer vision for defect detection. It’s also just fun to think about mass producing chocolate.

Background

You recently got hired as an Oompa Loompa software engineer working at Willy Wonka’s chocolate factory on a team that images chocolate accross the various stages of the manufacturing line in order to find defects. They use all sorts of fancy cameras: 2D, 3D, radiographs - they know their stuff. This approach lets them both find defects quicker than waiting till the end of the factory line to find out something’s bad, and also allows scrapping defective material much earlier in the manufacturing process to cut losses.

However, before we try and find defects in an image of a bar we’ve got to first find an area to search through for defects – otherwise a defect model might get confused and flag the background as defective. We’d also want constrain the defect search space as much as possible to make the defect model more efficient at flagging defects. I refer to this specific semantic segmentation task as “mask finding”.

For example, if your human neural network saw images in Fig 2. of bars-in-the-making, what features would you think distinguish it from the background? Maybe that a bar has four corners, is a different color than the background, and has a different surface consistency. If we as huamns can distinguish chocolate from it’s background we could probably write a rules based program for finding a segmentation mask, but the types of input images often rapidly changes:

- Oompa Loompa scientists may iterate on the product and future chocolates might have different dimensions

- imaging conditions of inspection stations may change (different light color, angle)

- we may want to use a different type of camera (laser profiler, darkfield black boxes)

All of which leads to a dizzying combination of image possibilities and you’d be playing a game of cat-and-mouse to keep up by writing separate image processing pipelines for each variation.

ML

So then how do we scale this process up for hundreds of thousands of images a month across multiple image and camera types? Universal Mask Finding is an ML model I trained while I was at the chocolate factory to solve this problem. The magic of deep learning is that we don’t explicitly program the model to find the features we just mentioned, we ask the model to hopefully learn them automatically across our dataset.

The model is based on an off-the-shelf U-Net segmentation architecture with pretrained resnet34 weights and infers a pixel-level segmentation mask. That means, for every pixel in an image the model predicts the probability that it belongs to the foreground, or background. I fine-tuned a pretrained model originally trained on the ImageNet task with the relevant images of chocolates. More about transfer learning here.

We measure the performance of a segmentation model based on the Intersection over Union score, or IOU, which is a fancy way of saying what % of the prediction overlapped with a ground truth label.

We can also do interesting things here with the inference probabilities like setting a lower threshold for the mask class like 0.3 to increase the recall (but at the cost of decreased precision).

Generalization

Often in machine learning we want a model to be able to generalize on a given task as much as possbile, and that’s probably a good marker that it’s learning something about the underlying nature of the problem. Somewhat counterintuitively, I found that I get the best performance by allowing a single model to learn features across all the varying “image types”. Examples of things I would separate into different “image type” categories include different cameras, backgrounds, and components.

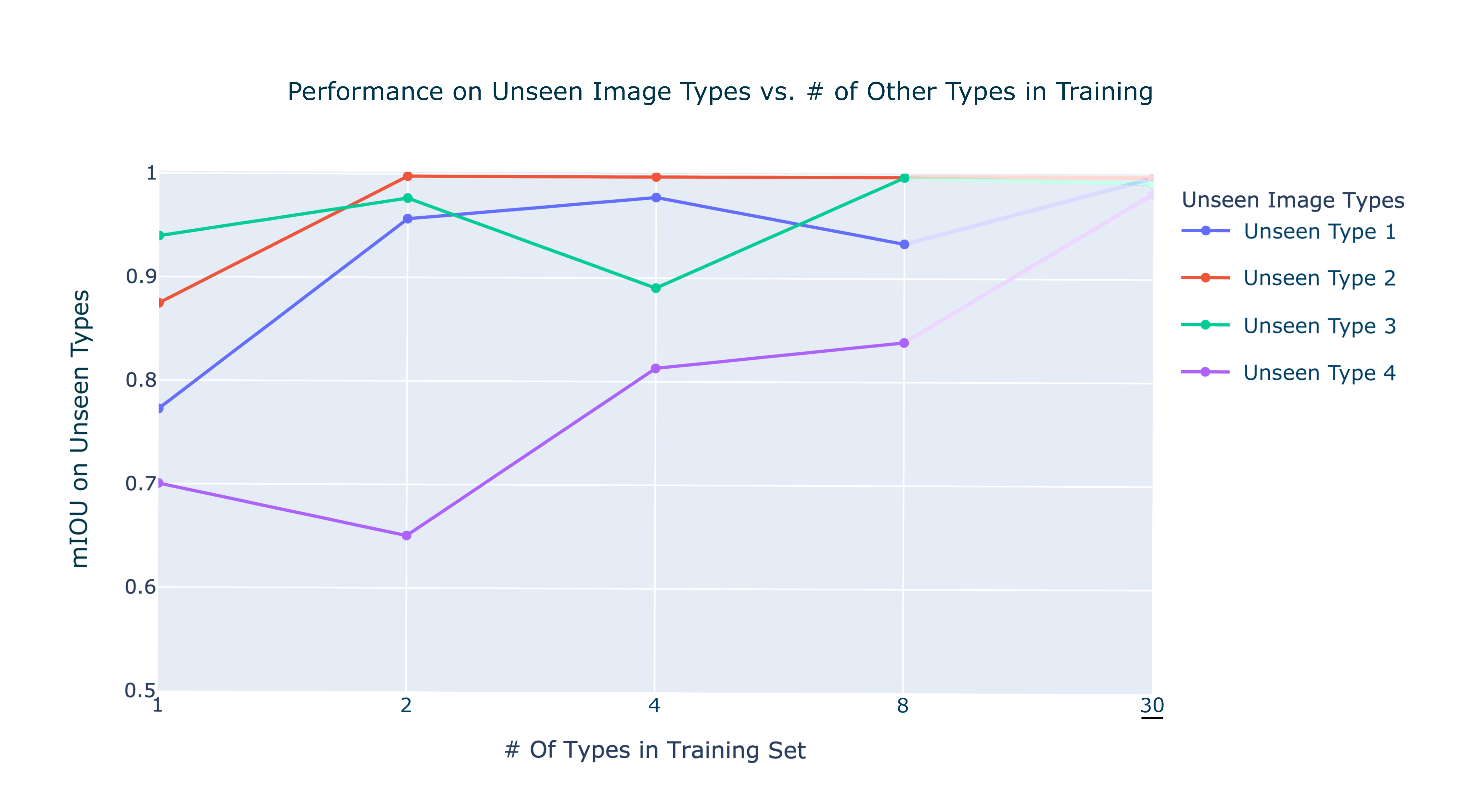

To prove the model generalizes well I ran a simple study where I gradually increased the number of image types in the training set, and measured performance against unseen image types.

And if we include all image types (dotted lines) during training we can close the gap to virtually perfect. This is particularly nice for two reasons:

- because there is a lot of uncertainty in incoming images in production

- because this approach saves Willy Wonka $$$ per month in server costs compared to deploying 40 different models for each image type

Building Trust: Classification Reviewer Model

Some fellow Oompa Loompa cocoa scientists asked me how they could trust my mask finding model’s inferences - a very fair question. I tried developing rule based metrics to see if a mask had 4 corners, straight lines etc. but it turned out to be a difficult task as no one criteria would capture the complexities of judging mask finding quality. I realized that a deep learning model classifier would outperform any handwritten metrics I could come up with. This new classifier would run after each segmentation prediction and would have 3 classes:

Because I already had ground truth human labels for the segmentation task I already had a great set of examples for Grade 1. All I needed to do was find a handful Grade 2 and 3 failures and to my surprise the classifier had an AUC of 0.995! We could now use the classifier’s predictions to understand whether or not to trust the segmentation model.

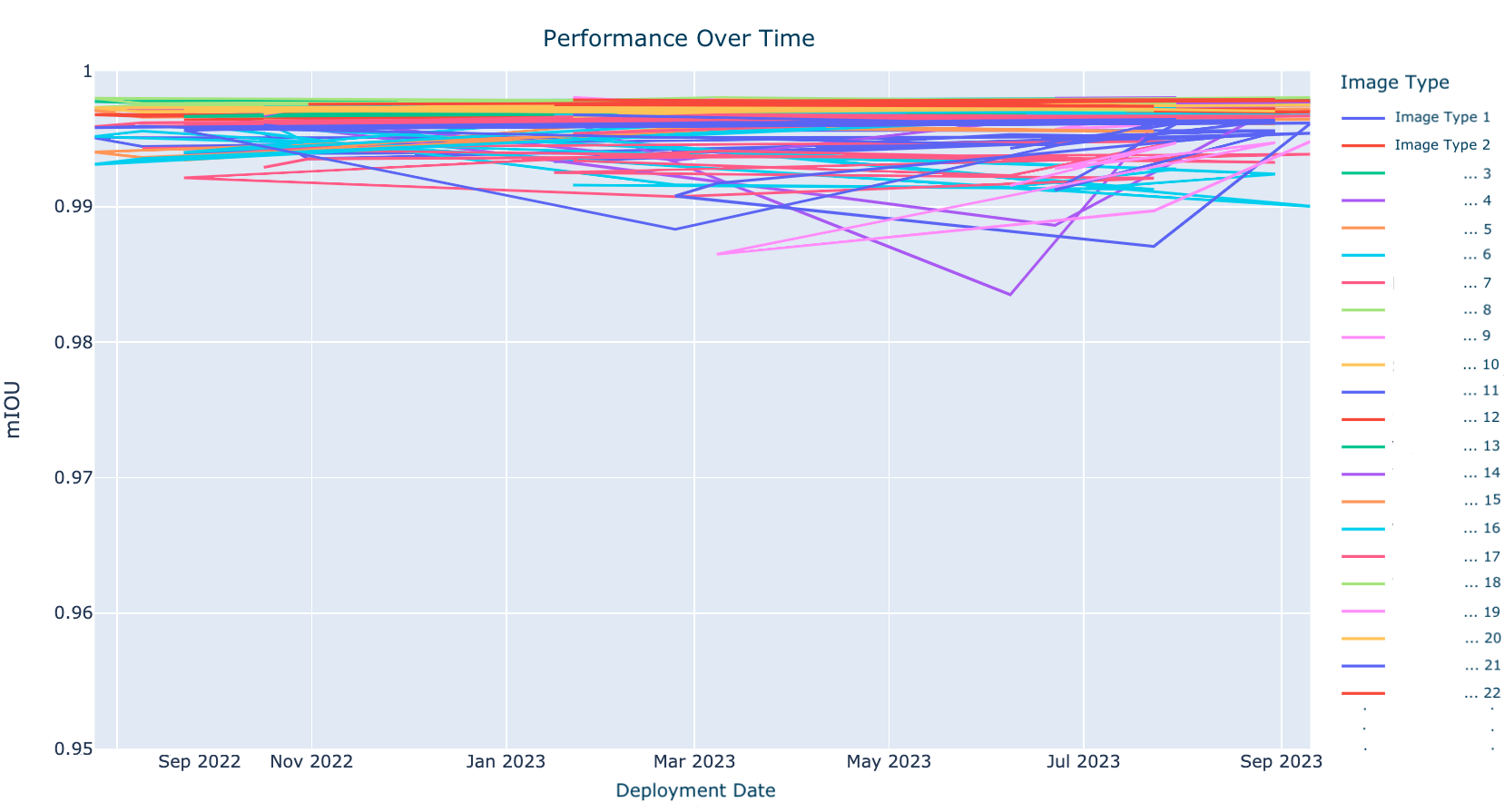

Building Trust: Historical Performance

To further build trust in the model I monitor how each image type, which is demarked by a metadata tag in the dataset, performs over time, making sure that all their respective mIOUs are close to 1. I also periodically check my historical data log to inspect how the model is doing in production and shuffle the dataset with the latest examples of failures. It’s very difficult for me to perfectly monitor this model in production and so I also rely on my fellow Oompa Loompa scientists and production managers to notify me if they notice a drop in inference quality.

In general the number of image types for the model to run on have only been growing so I typicially also evaluate a new model based on a previous iteration’s dataset just to double check that I’m not noticing a drop in quality for older image types. It’s also fun to evaluate an older iteration on the latest model’s test dataset to quantify the improvement.

I’m proud this ML system has been robust while integrating new cameras and chocolate types and was able to scale to help the chocolate factory grow while delivering the best chocolate possible.